Mesoamerica, Japan, and life in death

- Breanna Vinson

- Jan 23

- 5 min read

October 15, 2023

Historically, death has been seen in a multitude of ways, captivating humans for all of time as an inevitable great unknown. The fact of the matter is that all living things will die, yet what exactly happens to that individual is left a mystery. As such a mystery persists, various cultures have come up with their own view regarding fate at the end of life, and this phenomenon has been captured throughout the art scene. For this discussion, the treatment of the afterlife will be one examined through two differing cultures, Mesoamerica, and Japan.

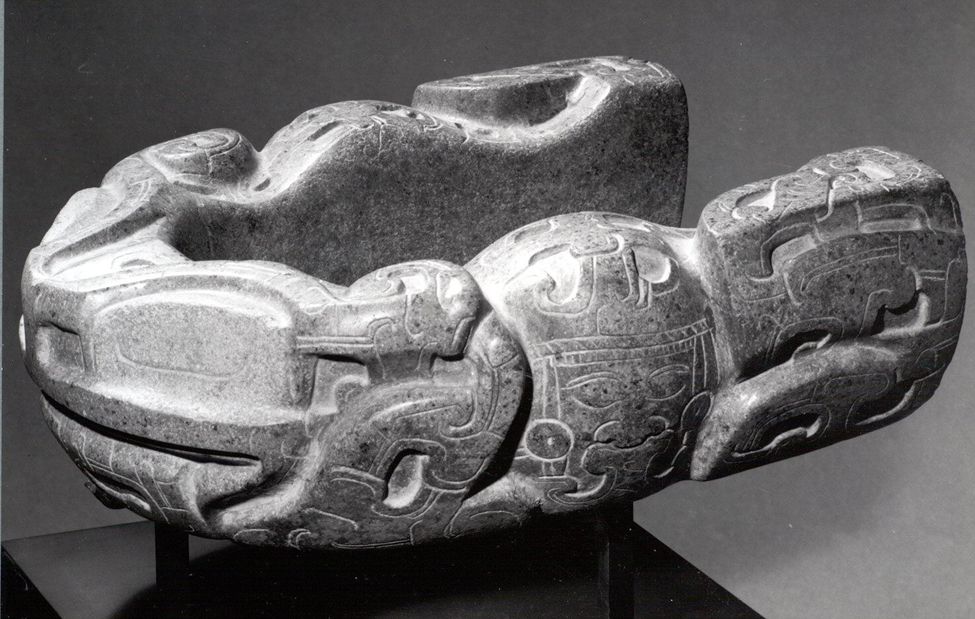

Notably, such a comparison is also one of the arts, and thus it is integral to integrate works from each area. To represent Mesoamerica, the artwork Frog Yoke has been chosen alongside Haniwa Figure of a Warrior, a representative work from Japan. Inspecting the art of Mesoamerica, the structure is an aspect of note, creating a U-shaped surface. Detailing this surface, eyes are made prominent in the front of the object, looking to be closed as the lid of the eyes are carved on an otherwise smooth surface. Between these eyes are the nostrils, formed by an etched square and resting just atop a large mouth. Such a large mouth is agape, parted by a curving tongue where patterns have been engraved.[1]

While much of this design has engraved patterns to it, the form of the frog’s legs are also engraved in the sides, further making such a creature clearly recognizable. Notably, a human face has been carved into the side, resting between the legs of the frog. A similar instance is also found at the end of the work, showing a face in side profile on either side, with a symmetry like that of the front facing illustration found on either side.

Returning to the U-shape of this carving, it is revealed that this artwork is that of an Aztec yoke. This yoke is not the type used to harness cattle and is simply named after such, harboring no other connection to such a thing.[2]

Rather, this yoke is representative of a uniform worn by many Mesoamericans in the playing of a game aptly called the ballgame, serving as a decorative ode to the event.[3] Not being worn itself, such a yoke was to be owned by important leaders and buried with them upon passing.[4] Such an aspect further speaks to the ballgame as an ordeal of great significance, serving as both a source of sport and entertainment, and one of ritual symbolism.[5] While there is little clarity on the rules, it is most evident the sport was taken with a sense of great prestige, taking up vast expanses of space with courts made specifically for such an activity. Additionally, the very material used to create this work was not naturally found within Veracruz, instead being imported from another area at a great expense.[6]

Looking at the patterns flowing throughout the structure, it becomes clear that the faces are meant to stand out, not following this purely geometric design and rather, creating a distinct image. To paint a picture of what these images represent, one must turn to the ritual aspects of the very ballgame this artwork is reminiscent of. Looking at the humanoid depictions, there are two instances of men with matching designs, most likely depicting the Popol Vuh, a K’iche’ Mayan creation myth. Such a myth has the narrative of two brother pairs playing the ballgame with the Lords of Xibala in the Underworld, the ballcourt serving as, “the setting for a mythological battle between the forces of life and death,” as understood by Caitlin C. Earley.4 Interestingly, the depiction of a frog ties into this narrative, being seen as a creature symbolic of transitioning between life and death.[7]

With the Haniwa Figure of a Warrior an armored individual is clearly depicted, having an oddly proportioned body, lacking features such as hands. While the inclusion of limbs is lacking, save for the stubby protrusions of arms, the figure has a clear face, sporting almond shaped cutouts for eyes and a smaller of the same for a mouth. The nose sticks out from the rest of the face, defining itself as a protuberance but not much more. Interestingly, the sculpted armor contains a deal of realism akin to armor worn by real soldiers, as if to serve as a replica.[8] With this work the base looks similar to a dress of some sort, although this is likely a matter of balance, distributing the weight more evenly as the base is larger. With the aspect of balance, the eyes and mouth being holes aid in this challenge, creating a hollow space, being an iconic aspect of Haniwa figures.

Detailed armor is an aspect of this work holding a deal of importance to it, as this artwork holds the duty of protecting those in the afterlife, according to the placement of Haniwa figures such as this. Additionally, the sentiment held for samurai comes into play, speaking to the positive reception from those with military positions. Not only is there an air of power from such figures, “many leaders of the military government became highly cultivated individuals,” creating a sense of grandeur and splendor.[9] While there is an aspect of uncertainty, an account from Dr. Yoko Hsueh Shirai reads, “instead of being buried deep underground with the deceased, haniwa occupied and marked the open surfaces of the colossal tombs.”8 Having a funerary object above the earth rather than in it with other objects of great value is purposeful positioning and speaks to the nature of something otherwise holding a notable deal of mysticism.

A less obscure bought of information regarding such a statue, is the varying subject matter held to the structures. While many were of warriors, horses and buildings have been found, along with simple cylindrical shapes. Interestingly, those constructed in the likeness of buildings were arranged within the tomb to resemble a village, guarded by the more common warrior figures. Such an arrangement may have had ritualistic connotations, although due to the nature of these artworks one cannot be certain.

Looking at both cultures, one can clearly see the prevalence of the underworld itself, serving as an answer to life after death. While both artworks are involved in the funerary process, the way they are integrated speaks to the culture. For the Mesoamericans, death was something to be fought against, the act of doing so one to be made into an event of triumph. Upon meeting their fate, the symbol of a what was once a victory was to be buried, becoming a treasure to take into the new life found in death. With the Japanese, death was something of peace, yet vulnerability. The mortal body was to be protected in order to ensure safety of being in the life found in death.

Haniwa Figure of a Warrior. Kofun period (ca. 300–710). Earthenware with painted, incised, and applied decoration. H. 22 7/8 in. (58.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/45545.

Frog Yoke. 7th–10th century. Greenstone, pigment (probably hematite). H. 5 x W. 14 7/8 x D. 15 3/4 in. (12.7 x 37.8 x 40 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/310471.

[1] Frog Yoke. 7th–10th century. Greenstone, pigment (probably hematite). H. 5 x W. 14 7/8 x D. 15 3/4 in. (12.7 x 37.8 x 40 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/310471.

[2] Frog Yoke, 0:09, 4.

[3] Smarthistory. The Mesoamerican Ballgame and a Classic Veracruz yoke. 2015. 3:38. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4dpE80AU-oI&t=4s.

[4] Smarthistory, 0:49, 5.

[5] Earley, Caitlin C. The Mesoamerican Ballgame. 2017. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/mball/hd_mball.htm.

[6] Smart history, 0:32, 5.

[7] Smarthistory, 2:20, 5.

[8] Dr. Shirai, Yoko Hsueh. Haniwa Warrior. 2015. Smarthistory. https://smarthistory.org/haniwa-warrior/.

[9] Department of Asian Art. Samurai. 2002. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/samu/hd_samu.htm.

Comments