The idealized face in Ancient Greece and Rome

- Breanna Vinson

- Jan 23

- 5 min read

September 21, 2023

Artwork of Greece and Rome were greatly influential in the art world, and thus hold a great deal of significance. Because of this fact, one may see the two as largely the same, but this is not so. While there are aspects present in both, it does not negate the factor of differences between the two. In order to illustrate this point, two works will be examined and compared; One from Greece, and the other from Rome respectively. It is worth noting that to better understand how the works relate to each other, those selected are of similar subject matter and medium. To begin this analysis, the first step is to look at each piece as it is, without comparison to an outside work. Understanding something on its own is the first step to understanding it in relation to other things.

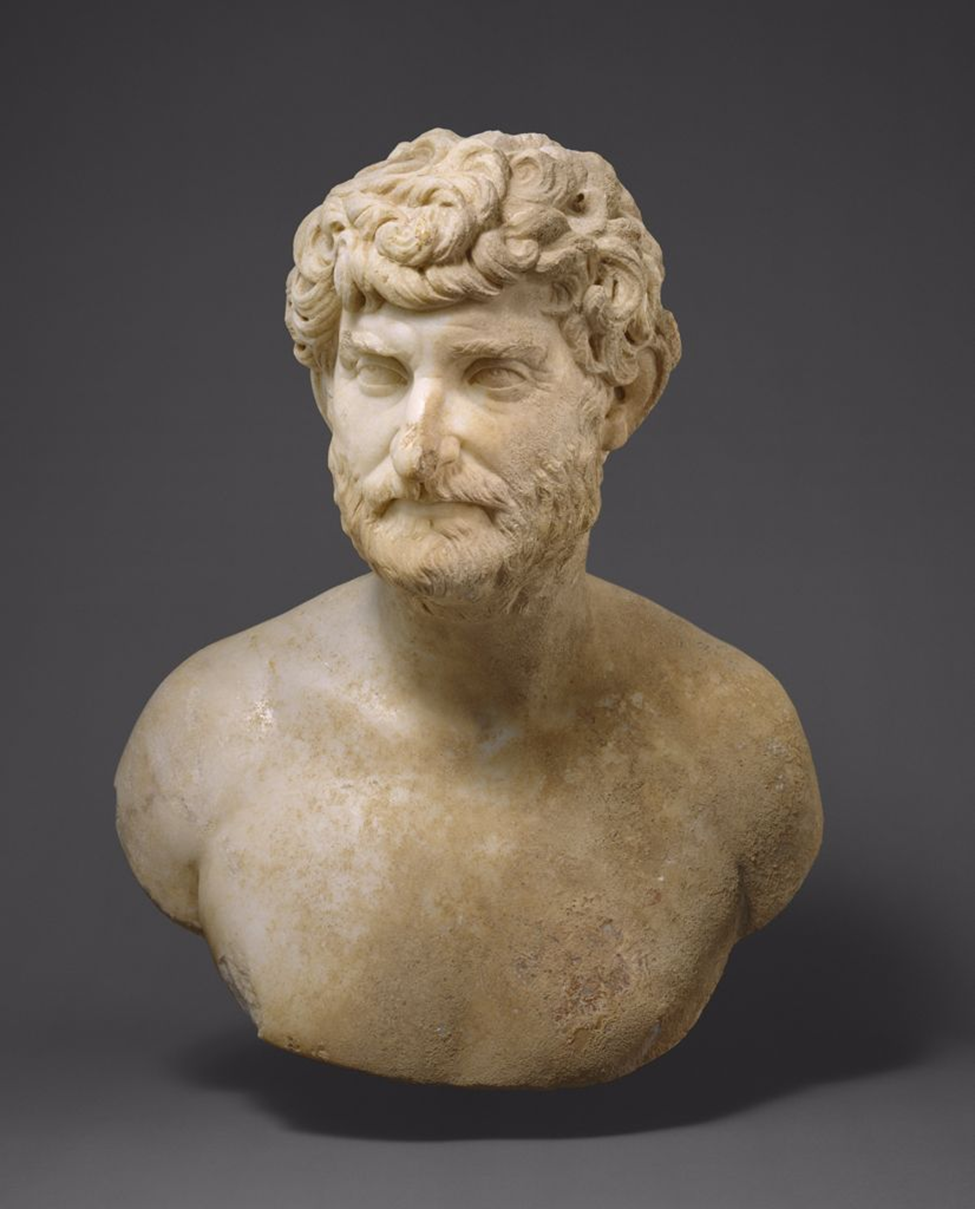

To begin, the statue representative of Rome depicts a bearded man whose hair has tight curls, too short to obscure the forehead, save for a small portion at the top. The beard itself sticks close to the face, too short to stray, and accompanied by a well-groomed moustache. Rather than be cut off at the neck, this sculpture is rounded to an end towards the pectorals, showing most of but not all of the chest. Additionally, the shoulders are also included. Wrinkles are attributed to the face, being clearly visible in addition to other areas of facial definition. These wrinkles border on verism, a term Dr. Jeffery A. Becker defines as, “A sort of hyperrealism in sculpture where the naturally occurring features of the subject are exaggerated, often to the point of absurdity.”[1] Intricate details such as this are what give this construction the look of realism, depicting a feasible individual.

This depiction is not far from what commonly prompted such sculptures, as a particular funeral procession included the creation of a bust as commemoration for high ranking individuals, among other memorabilia.[2] In order to best represent someone, the essence must be captured in general proportions, but intricate details such as this elevate the likeness to a even greater degree of realism. Beyond this particular scenario, wrinkles were seen as a symbol of status, representing seriousness and virtue. Dr. Jeffery A. Becker remarks that, “The subject literally wears the marks of his endeavors,” putting into perspective the significance of this detail.1

The Greek work chosen for this comparison is of a woman’s head, having short wavy hair that follows down the neck. It is notable that the cutoff at the neck doesn’t appear to be intentional, likely having broken due to the age of the terracotta. This brings into question what the rest of the body would have looked like, and if it were to have a more naturalistic construction or a static pose. Additionally, the ears of this woman are adorned with earrings of some kind, a dark dot being in the center of the ear lobe with an arrow shape dangling from it. The face is somewhat simple, showing clear features and symmetry yet having the slight smile found in kouroi and korai statues, which end up giving the figure a strange, hard to explain expression. This can be perceived as a lack of expression, due to the oddness of it.

Notably, the facial features themselves do not appear to be specific to an individual, having a generalized human look. This more stylized approach is common among kouroi and korai statues, emulating the art of Egyptians.[3] These statues have a difference of name depending on the depiction of a man or woman. For woman the singular would be kore and the plural korai, whereas men have the singular kouros and plural kouroi.[4] Looking at the face one can infer this to be part of a kore statue, due to the idealized image shown. Interestingly these statues were created as a display of youthful perfection, a quality valued by the Greeks so greatly that as Erin Thompson puts it, “The best time to die was when you were young and beautiful. You’d never have to know the indignities of growing old.”[5]

Interestingly, art hailing from Greece has parallels to the precise architecture of the time.[6] This is due to the emphasis on symmetry, something taken particularly seriously in architectural works. Colette Hemingway aids in putting such into perspective, stating the architect’s role as one, “Who participated in every aspect of construction.”6 This tidbit is relevant to the terracotta statue as it further shows the emphasis on symmetry. Although intricacies of detailed facial features are moot, precision is found within this uniformity.

Both depicted works say something about their place of origin. Interestingly, these depictions come with opposing views on age, showing the ideal age for each respective culture. The Romans saw age as a marker of endurance and had a preference for sober, realistic portraits, seeing them as a way to illustrate the fruitfulness of a long life.[7] The Greek saw youth as the prime time of an individual’s life, seeing it as a privilege to die young rather than to face the degradation of old age. Moreover, these held sentiments differ greatly, and show separate identities. Even with such differences it is important to note the aspects of similarity, showing how something can be vastly intellectually different from another artwork, yet maintain similar visual aspects. The most prominent similarity is the very nature of these two works, showing an idealized image of their respective culture with human form. These artworks hold the same premise, representing the same subject matter, and it is the ideology of the two cultures that drives the visual differences.

Fig 1. Marble bust of a bearded man. Ca. A.D. 150-175. Marble. 22 in. (55.9 cm). Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://library.artstor.org/#/asset/MMA_IAP_1039651697;prevRouteTS=1694729564359;iap=true

Fig 2. Terracotta head of a woman, probably a sphinx. 1st quarter of the 5th century B.C. Terracotta. 8 1/8 in. (20.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://library.artstor.org/#/asset/MMA_IAP_10311575704;prevRouteTS=1694736331767;iap=true.

[1] Dr. Becker, Jeffery A. Head of a Roman Patrician. 2023. Smarthistory.

[2] Trentinella, Rosemarie. Roman Portrait Sculpture: Republican through Constantinian. 2003. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/ropo/hd_ropo.htm.

[3] Dr. Herring, Amanda. Pottery, the body, and the gods in ancient Greece, c. 800-490 B. C. E. 2022. Smarthistory. https://smarthistory.org/reframing-art-history/pottery-body-gods-ancient-greece-early/.

[4] Bulger, Monica. Kouroi and Korai, an introduction. 2021. Smarthistory. https://smarthistory.org/kouroi-korai/.

[5] Smarthistory. From tomb to museum: the story of the Sarpedon Krater. 0:44. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fzorm4Q_vuk.

[6] Hemingway, Colette. Architecture in Ancient Greece. 2003. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/grarc/hd_grarc.htm.

[7] Marble bust of a man. 0:35. Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/248722.

Comments