Women in the 20th century

- Breanna Vinson

- Jan 23

- 16 min read

December 13, 2023

Throughout the history of art, people of varying backgrounds have been depicted. From royal portraits to fabricated strangers, illustrating the human figure fundamentally speaks to how those individuals are perceived and what characteristics are attributed to specific identities. Interestingly, cultural factors play a significant role in perceptions; this fact is one that will be explored regarding how it impacts women. To better understand how the image of womanhood is shaped, it is integral to factor in the time period, as this definition differs based on societal factors dependent on such. For this discussion, the allotted time is the eighteen hundreds, also known as the modern age, and a time of change for women’s roles. With these details in mind, this writing focuses on how women are represented in artwork and how this depiction speaks to womanhood of the time. Additionally, the cultures of America and Japan are to be examined, expanding upon how culture has a significant role in shaping what a woman is expected to be. Within such contexts, the lens of feminism is most appropriate, so it will be the theory utilized within this writing.

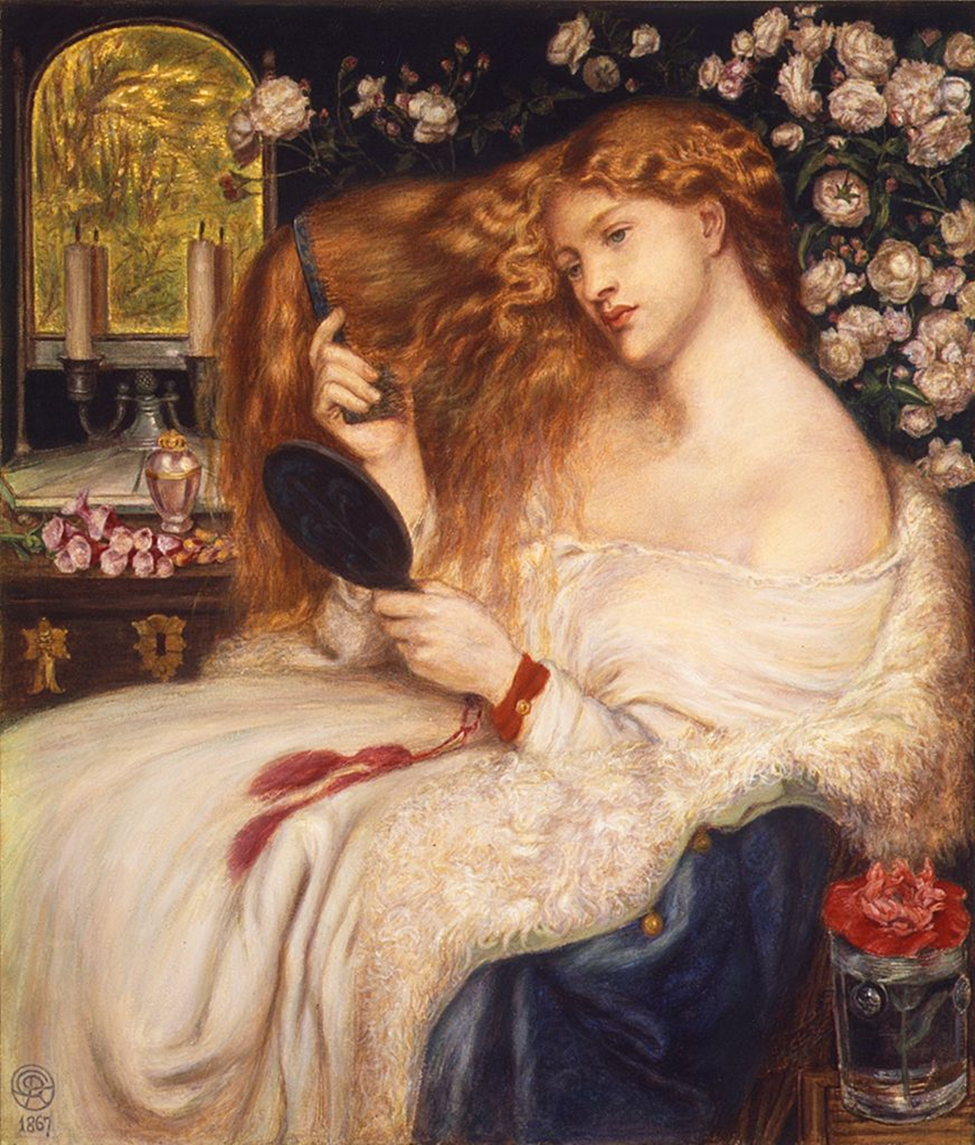

Regarding the chosen cultures, Japan and America, these are two vastly different areas representing the East and West respectively. This comparison poses two major questions ---what it means to be a woman in twentieth-century Japan and what it means to be so in twentieth-century America. Harkening to the concept of an identity being captured in a rudimentary way through illustrations, a formal analysis is to be performed on both artworks chosen for discussion, allowing for a surface-level analysis that doubles as an introduction to the subject matter. These artworks are Lady Lilith (Fig. 2) from Western artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Woman Spinning Silk (Fig. 1) from Eastern artist Katsushika Hokusai. Both paintings feature women as the center of the work, an aspect integral to the discussion at hand.

With the chosen artwork of the East, Woman Spinning Silk (Fig. 1)[1], the focus is, as the title implies, depicting a woman as she spins silk. This composition is notable as the scene depicted only contains one purely decorative design element, not an element necessary for the narrative shown. However, the aspects integral to the setting are materials needed to spin silk, a chair, the woman of focus, and, interestingly, a young girl observing the proceedings. With the positioning of the woman in this artwork, it’s clear she is actively partaking in the shown duty, leaning into the structure with her hair tucked up and out of the way of such actions. Additionally, the clothing worn by the woman of focus depicts a simple design, one lacking grandeur and instead showing practicality. The same cannot be said for the young girl in the art, as she has a notably more elaborate pattern, which is much shorter and less practical for simple actions such as sitting. As for the aspect with no apparent connection to this scene, three or perhaps four birds are shown to be flying above, each looking to be facing a different direction.

As for the chosen Western artwork, Lady Lilith (Fig 2.)[2], a woman is depicted in an elaborate scene, combing the curls out of her hair while holding a mirror. Clothed in an elegant white dress, she is seated at what appears to be a vanity, a perfume of sorts resting on it, along with some flowers, a decoration present throughout the artwork. Her hair is long and notably lustrous, having a golden orange coloring that makes such a feature striking, drawing attention not only to the action of the combing but to the hair itself. The face of the woman shown has a serenity to it, strengthened by the reclined positioning and somewhat by the dress falling off the shoulder. Interestingly, her face has no makeup, possibly indicative of natural beauty. Notable aspects of the surrounding scene primarily consist of the abundance of floral decoration present in much of the composition. This further emphasizes beauty, surrounding the woman with notoriously pretty blossoms, a decoration that innately brings with it the aspect of natural beauty.

With illustrations of the human figure, an aspect of note is evident in the high standards of craftsmanship in which a sculptural portrayal is desired and anatomical mastery is demanded.[3] While this isn’t the focus of the discussed artworks, it is important to note, as such expectations directly aid in a more realistic portrayal of being human. This is most evident anatomically, giving the individual themselves greater depth. With an accurate depiction of the body, there also comes a depiction of perceptions regarding what the figure is or is meant to be. In the case of these illustrations, that individual is evidently one of a woman, and with that in mind, the question arises of what these artworks say about the women depicted. How does the lens of feminism impact the perception of the person?

Feminism itself holds the belief that “full social, economic, and political equality” should be present among women.[4]

While the fight against inequalities is prominent, there is also an emphasis on how unequal laws, treatments, or expectations affect women. With an analysis of art, the topic of equality is not often the focus, and instead, how women are depicted and perceived is of note. The work often speaks more to a general perception of women if the artist is male. However, if the artist is female, the experience of being a woman is generally more focused on. For both chosen artworks, a facet of note is that both artists are men, lacking a personal connection to womanhood.

The first of these (Fig. 1) tells of the role women had within society by simply including a young girl. While compositionally, this is an inherently ambiguous choice, the social structure of this time implies a familial relationship between these two figures. Specifically, one of a mother and daughter. This element speaks to motherhood as an aspect of heavy focus regarding the place of Japanese women, bringing with it curiosities regarding how prominent such an aspect of life was for these women. Interestingly, this narrative sees reinforcement with advances in equal education. While this may initially seem unrelated, it quickly becomes apparent with “Good Wife-Wise Mother” schooling being one of the earliest schools for women specifically, showing a clear bias towards such avenues.[5]

Not only does this create an environment not fully open to the developing goal of “equal education,” it actively reinforces the expectation of childcare and homemaking.

These expectations saw such a significant emphasis that upon looking into these women's lives, the topics of marriage and family were the first to see research.[6] While this prospect was a large portion of many women’s lives, it came with a lack of control. This aspect fell into the more classical gender roles of men being leaders and women being followers. While this system is not inherently damaging in all scenarios, it brings forth a concerning distribution of power, in this case going so far as to withhold the ability for a woman to initiate or feely consent to marriage or divorce.[7] Instances where trouble arose were often inescapable for the trapped women. A poem by Kathrine Phillips conveys this with the writing,

“A virgin state is crowned with much content,

It's always happy as it's innocent.

No blustering husbands to create your fears,

No pangs of childbirth to extort your tears,

No children's cries for to offend your ears,

Few worldly crosses to distract your prayers.”[8] This scenario created from this forced dynamic results in submission not only being expected but also being the designated way of life for those within a married relationship, causing this relationship to be most akin to that of a servant obeying her master. This sentiment is best put with the expectation that “a woman at every stage of her life must obey her father as a daughter (1), her husband as a wife (2), and her sons in widowhood (3).”[9]

Interestingly, the topic of sexuality was somewhat demonized. With this prospect, geisha were often targets of scrutiny, a figure often depicted within contexts such as social issues, creating issues for middle-class reformers and bureaucrats. These troubles were created as the very concept of a woman working in the sex trade went against the virtues of monogamy that had heavy prominence.[10] A widely held sentiment regarding such work was one where these women were sellers of their bodies, the sex trade itself an “evil custom of the past.”[11] This statement indicates the shift in the roles of geisha, a turn towards enlightenment following the resulting decline in prostitution. The rise of “enlightened” geisha created less disdain around this line of work while simultaneously causing a more significant shift towards education for women. While this produced a positive for those who previously were unable to receive education, the motives behind this change were still rooted in negative views toward geisha. A letter to the editor of Yomiuri shinbun newspaper reads “that if Tokyo did not establish more schools for women, girls from good families in the capital would not be as accomplished as prostitutes from Kyoto.”[12]

Luckily, as the modern age progressed, women in Japan saw a less rigid structure and more opportunities to become independent. As briefly mentioned earlier, education saw significant change during the twentieth century, with the idea of “similar or equal education for both sexes” seeing considerable traction.[13] While it is undeniable the start of such a goal saw trouble in providing unbiased teachings, from around eighteen seventy-two to eighteen seventy-nine formal education sought to broaden women's perspectives, implementing an aptly named system of “new learning.”[14] Rather than discourage something as integral as reading, this new wave of schooling included encouragement in such areas, providing students with a significantly more enjoyable experience. Additionally, “by nineteen-twenty, the fight for women’s political inclusion was at the forefront of the suffrage movement,” resulting in achievement of this goal in nineteen-twenty-one.[15] While these progressions provide significant progress, bias still held a heavy presence, evident primarily within higher education. As decreed by the Ministry of Education officials, the goal of women's education had yet to shift from the ideal of “producing good wives and wise mothers.”[16]

Due to the subject matter of the chosen illustration being one that shows this woman actively creating, it can also be seen as reminiscent of women in the workforce. While there was yet to be equal footing within this area, “women played a surprisingly powerful role in early classical times,” a sentiment that sees prominence with the inclusion of toji and grand tojo known as ōtoji.[17] These roles aided in labor supervision, providing a system of organization for significant activities. While not a major movement, it is important to note advancements in gender equality, showing that women saw more consideration with the progression of time.

While true equality was not present in the twentieth century, opportunities for women began to flourish, a fact the art of Woman Spinning Silk (Fig. 1)[18] shows in its depiction of a woman who has presence within the workforce. Interestingly, the shown task speaks to the very nature of rising education, most training being rooted in “sewing and other practical household skills that would ready them for marriage.”[19] This resulted in a landscape where women were expected to be subservient to their husband, but a closeness was not necessarily commonplace. While it was taboo for a married woman to participate in prostitution, the family typically consisted of loose ties between wife and husband but strong ties between the mother and her children.[20] This strong connection with her children partially resulted from the mother’s prominence in their lives, as it was rare for fathers to be notable caretakers. While there were women with positions of power, this was a rarity, becoming more common as the years progressed. In this way the role of Japanese women was one seeing change, most notably with the shift in education as subjects became less rooted in traditional women’s roles and greater access to this education.

With the artwork of Lady Lilith (Fig. 2), it is immediately apparent that the focus is on the depicted woman, having her take center stage.[21] The combing of her hair is reminiscent of beautification, an act that aims to bring forth a greater sense of beauty through making improvements to appearance. While something as simple as tending to hair may not appear to be monumental, with the medium of art, each detail is one of intention, and as such, this is no different. With such a facet in mind, this compositional choice speaks to the changing beauty standards, bringing with it a greater emphasis on appearances. Not only was this narrative of a “new woman” pushed by magazines such as Good Housekeeping and Vanity Fair, but it also brought new idealized types of women to focus.[22] Specifically, the picture of women at this time grew to become one of “a multi-faceted type, always at ease and fashionable.”22

While this idealization sounds like a largely positive narrative, the title of this piece points to an underlying element of caution with the name Lilith. This name can be found in Jewish mythology and folklore, referring to “a raven-haired demon who preys on helpless newborn infants and seduces unsuspecting men.”[23] The element of seduction pits beauty as a dangerous weapon, being a lure to men into an otherwise undesired relationship. With the mythos of Lilith, this comes into play when, after having submission insisted upon her, Lilith revolts and replies, “We are both equal, for both of us are from the earth.”[24] This suggestion of equal footing for both men and women brought forth outrage as it defies the dynamic of women being innately submissive to men, seeing relevance in the time of the modern era as, despite advancements in women’s rights, men were still seen as the dominant force meant to be above women in command.

The dynamic of men being in power over women reinforced the narrative of the married woman being idealized not only for the women themselves but for their spouse. Often, this idealization created an environment with a lower quality of life for single women, forcing them to face social degradation while being valued as much lesser than that of a wife or even a widow.[25] Causing those that chose not to wed to become social outcasts, this often resulted in women throwing themselves “into the "vilest" marriages just to avoid being single.”25 Additionally, women’s rights were severely lacking, as legally speaking, there was a drastic imbalance between men and women. This discrimination had been persistent for many years, being a longstanding issue.

However, to the relief of those affected, a level of intolerance rose, bringing forth the women’s rights movement. Foundations for the changes that followed were rooted in the sentiment that “whatever is right for men to do is right for women,” resulting in a push to abolish the present inequalities.[26] The changes fought to achieve the right to vote saw a significant push. Other elements regarding the experience of being a woman included “politics, work, the family, and sexuality.”[27] Efforts such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s organization of the first women’s rights convention were integral to the resulting impact of the aforementioned movement.[28] An important detail to note regarding such changes was that while the quality of life for many women increased, it did not fully resolve all the present inequalities. The mention of such is notable as it indicates the changing times and the landscape attributed to it.

This shift caused the maintenance of a household and the care of children not to be all a woman could do, according to society. These demanding, unpaid tasks were seen as “women’s work,” an expectation of women that persisted for years.[29] Luckily, with the women’s suffrage movement, women could enter the paid labor force and receive monetary compensation for their efforts.28 While the ability to find employment was a vast improvement for those looking for another way of life, it came with another set of troubles. Put simply, inequalities rose in the form of wage gaps, creating another issue to fight against. Interestingly, the rise of these jobs was undoubtedly influenced by wars, providing another avenue for those struggling to earn a living wage.

With more opportunities and a greater sense of individuality, the women of this time had a greater show of independence. This self-expression and pursuit of new possibilities meant the life of a wife and mother did not seem like the only feasible option, and other paths could be followed. The progressions within society meant “it was possible for an unmarried woman to have a varied, interesting, useful and fulfilled life.”[30] This positive narrative was also present with the image of Rosie the Riveter, a woman shown “rolling up her sleeves in a strong, confident pose, exclaiming “We Can Do It!””[31] Indicative of those newly joining the workforce, Rosie encouraged those who made such a decision. Additionally, this iconic image works as a sign of the times, particularly in that she still upheld traditionally feminine aspects within her appearance.

As the times changed, women were no longer only housewives who cared for children but were able to be independent individuals. Standing up for their rights, “the women’s rights movement achieved much in a short period of time,” no doubt aided by the passion behind the desire for change.[32] This push for such changes showed that women could hold power, creating a threat to men who previously had control over them in most areas. An important thing to note is that while many women took full advantage of their newfound opportunities, there were those who happily stuck with married life. This creates an interesting split, where roughly two sides of womanhood existed simultaneously.

This duality of experience creates a more complex definition of what a woman’s role is due to the increased freedom of choice paired with a greater level of opportunity. With such variables, it is plausible that the role of a woman is one with fluidity, not set in stone in the ways it was previously. To quote Martha H. Kennedy once more, the “new woman” was “a multi-faceted type,” having more confidence as she saw new freedoms.[33] These shifts in environment resulted in two distinct paths a woman could take, this choice dictating what role she found. These two choices consisted of life as a housewife and caretaker to one’s children or an independent worker seeking self-sufficiency. Although each side has a particular way of life attributed to it, it is essential to remember that in many cases, the role taken was one with aspects of each. Thus, an unbalanced distribution of elements was more common than a total lack of one extreme.

As for the role of the Japanese woman, similar plights arise when aiming to define a singular role. Interestingly, the role women have sees a notable shift as time progresses, rather than having two prominent roles. At the start of the twentieth century, women were to be housewives, subservient to their husbands, whom they typically relied on monetarily. While this role is one most societies instill upon women at one time or another, there is some nuance to the lives of these women. Rather than be reduced to wives and nothing more, some upheld leadership positions, indicative of “an enhanced appreciation of the position of women.”[34] These women of power were explicitly not to be regarded as “wives” at all, giving them a sense of individuality.34

This narrative sees expansion as years progress, schooling reaching new levels of accessibility to women as enlightenment becomes a priority. While at first glance, the shift towards education creates an entirely new role, this is not so due to the nature of women’s schooling. Education Minister Kabayama Sukenori “announced that the purpose of education in higher girls’ schools was to produce “good wives and wise mothers,”” a statement telling of the still deep-rooted inequalities.[35] While moving from the role of subservient wife to one with higher autonomy and education is a net positive, it is important to note that this education had yet to give women equal standing to their male peers.

While all the details of these stories are not evident at a glance, the art of Katsushika Hokusai and Dante Gabriel Rossetti speak to the roles of women previously mentioned. Lady Lilith (Fig. 2) centers around the new freedom women had, allowing them greater self-expression and power, no longer stuck to the role of housewife if discontentment for such was present.[36]

However, this picture of a confident woman comes with an implied caution in the title itself, as the name Lilith connects back to a demon goddess with a deceptively alluring appearance.[37] Such implications likely stem from the threat this new freedom posed to traditional gender roles, taking away a level of power men held for a longstanding period. “The idea that marriage and motherhood are the only routes to happiness” not only becomes a sentiment with substantial subversions, but the option to oppose such no longer sees sparse plausibility, giving women the chance to achieve self-fulfillment “without the protection of a male.”[38]

As for the snippet Woman Spinning Silk (Fig. 1) provides, a new wave of opportunity arises with women having a greater presence as a focus around equality forms.[39] “The role of the woman as a character who takes care of the house and children” remains present in all aspects of a Japanese woman’s life, but the challenges against such see significant growth over this period.[40] The most notable area of change is in education, innately allowing for more opportunities as men no longer held an upper hand in such an aspect. Although schools had biased teachings, foundations for a brighter future were laid. Looking at how this presented itself in a specific example, “encouragement rather than discouragement or censorship of extracurricular reading was Chise's experience,” and “Chise's formal education sought only to broaden and widen her perspectives, never to limit them.”[41] Looking back at Woman Spinning Silk (Fig. 1), this expression of a hopeful future can be seen as a young girl watches a woman, presumably her mother, as she creates.[42]

In short, the experience of womanhood frequently sees the element of motherhood or the title of wife, often focused on to a greater degree when such an experience is depicted from a man’s point of view. While the art discussed shows such elements, these roles alone no longer define what a woman’s life is to look like. As time progresses, freedom from a set expectation presents itself, significantly aided by efforts from the directly affected persons. This rising opportunity results in not one definition of a woman’s role, but rather, a set of general outlines that tell of experiences. For women of America, their experience was one of new freedoms and an ability to choose a domestic life or a more individualized life. As for the women of Japan, new opportunities arose in the growth of educational pursuits, creating a greater level of equality but not quite reaching the levels of freedom seen by those of America.

(Fig. 1) Katsushika Hokusai. Woman Spinning Silk. Hanging scroll; ink and color on silk. 1615-1868. Artstor. https://library.artstor.org/#/asset/MMA_IAP_10310749975;prevRouteTS=1698255329409;iap=true.

(Fig. 2) Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Lady Lilith. Watercolor and gouache on paper. 1867. Artstor. https://library.artstor.org/#/asset/AMICO_METRO_103824753;prevRouteTS=1698262720209.

[1] Katsushika Hokusai. Woman Spinning Silk. Hanging scroll; ink and color on silk. 1615-1868. Artstor. https://library.artstor.org/#/asset/MMA_IAP_10310749975;prevRouteTS=1698255329409;iap=true.

[2] Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Lady Lilith. Watercolor and gouache on paper. 1867. Artstor. https://library.artstor.org/#/asset/AMICO_METRO_103824753;prevRouteTS=1698262720209.

[3] Bambach, Carmen. Anatomy in the Renaissance. 2002. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/anat/hd_anat.htm.

[4] Brunell, Laura & Burkett, Elinor. feminism. 2023. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/feminism.

[5] Tsurumi, Patricia E. The State, Education, and Two Generations of Women in Meiji Japan, 1868-1912. pp. 9. 2000. Jstor. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42772154?searchText=&searchUri=%2Faction%2FdoBasicSearch%3FQuery%3Dwomen%2Bin%2B1800%2Bjapan&ab_segments=0%2Fbasic_search_gsv2%2Fcontrol&searchKey=&refreqid=fastly-default%3Ab8bf1e431a2e0b94fbf3f0b6e0f6266f&seq=1.

[6] Akiko, Yoshie & Goodwin, Janet R. Gender in Early Classical Japan: Marriage, Leadership, and Political Status in Village and Palace. pp. 442. 2005. Jstor. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25066400?searchText=women%27s+role+in+1800+japan&searchUri=%2Faction%2FdoBasicSearch%3FQuery%3Dwomen%2527s%2Brole%2Bin%2B1800%2Bjapan%26pagemark%3DeyJwYWdlIjoyLCJzdGFydHMiOnsiSlNUT1JCYXNpYyI6MjV9fQ%253D%253D%26groupefq%3DWyJzZWFyY2hfY2hhcHRlciIsInJlc2VhcmNoX3JlcG9ydCIsImNvbnRyaWJ1dGVkX2F1ZGlvIiwic2VhcmNoX2FydGljbGUiLCJyZXZpZXciLCJjb250cmlidXRlZF90ZXh0IiwiY29udHJpYnV0ZWRfdmlkZW8iLCJtcF9yZXNlYXJjaF9yZXBvcnRfcGFydCJd&ab_segments=0%2Fbasic_search_gsv2%2Fcontrol&refreqid=fastly-default%3A81c058d9a208de2adeeaf2f3d9521751&seq=1

[7] Tsurumi. pp 9. 4.

[8] Bild, Aída Díaz. Mrs. Fielding: The Single Woman as the Incarnation of the Ideal Domestic Women. pp. 57. 2017. Jstor. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26330870?searchText=women+in+1800&searchUri=%2Faction%2FdoBasicSearch%3FQuery%3Dwomen%2Bin%2B1800&ab_segments=0%2Fbasic_search_gsv2%2Fcontrol&refreqid=fastly-default%3Af0073d487b772f8a05116c98f991b956&seq=2.

[9] Karaoğlu, Semiha. The Evolution of Japanese Women’s Status Throughout History and Modern Japan’s Question: Are Japanese Women ‘Empowered’ Today? pp. 3. 2018. https://hcommons.org/deposits/item/hc:31393/. Humanities Commons.

[10] Stanley, Amy. Enlightenment Geisha: The Sex Trade, Education, and Feminine Ideals in Early Meiji Japan. pp. 540. 2013. Jstor. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43553525?searchText=&searchUri=%2Faction%2FdoBasicSearch%3FQuery%3Dwomen%2Bin%2B1800%2Bjapan&ab_segments=0%2Fbasic_search_gsv2%2Fcontrol&searchKey=&refreqid=fastly-default%3A99ec58ff7909e8227442821ee8185a7b&seq=1.

[11] Stanley. pp. 547. 5.

[12] Stanley. pp. 550. 5.

[13] Tsurumi. pp. 4. 3.

[14] Tsurumi. pp. 14. 3.

[15] Karaoğlu. pp. 10. 4.

[16] Tsurumi. pp. 20. 4.

[17] Akiko & Goodwin. pp. 437. 4.

[18] Katsushika. 2.

[19] Tsurumi. pp. 5. 4.

[20] Akiko & Goodwin. pp. 443. 4.

[21] Rossetti. 2.

[22] Kennedy, Martha H. American Beauties: Drawings from the Golden Age of Illustration. Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/beauties/overview.html.

[23] Roos, Dave. The History of Lilith, From Demon to Adam’s First Wife to Feminist Icon. 2021. Howstuffworks. https://people.howstuffworks.com/lilith.htm.

[24] Roos. 8.

[25] Bild. pp. 56. 5.

[26] Women’s Roles and Rights in the 1800s. Newsla. https://www.atlantahistorycenter.com/app/uploads/2021/01/EDU_SchoolTours_Cyclo_TeacherGuide_Components_Womens-Roles-and-Rights-in-the-1800s-.pdf.

[27] Burkett, Elinor. women’s rights movement. Encyclopedia Britannica. 2023. https://www.britannica.com/event/womens-movement#:~:text=https%3A//www.britannica.com/event/womens%2Dmovement.

[28] Newsla. 9.

[29] Shifting Gender Roles. Georgia College & State University. https://www.gcsu.edu/sites/default/files/documents/2021-07/Copy%20of%20Shifting%20Gender%20Roles%20-%2020th%20Century%20.pdf.

[30] Bild. pp. 68. 5.

[31] Georgia College & State University. 9.

[32] Elinor. 9.

[33] Kennedy. 8.

[34] Akiko & Goodwin. pp. 438. 4.

[35] Tsurumi. pp. 21. 4.

[36] Rossetti. 2.

[37] Roos. 8.

[38] Bild. pp. 68. 5.

[39] Hokusa. 2.

[40] Karaoğlu. pp. 14. 4.

[41] Tsurumi. pp. 14. 4.

[42] Hokusai. 2.

Comments